[Ed. note: This review was first published in conjunction with Cryptozoo’s release at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival. It has been updated for the film’s streaming release.]

Logline: In a world secretly full of mythical monsters, three women attempt to round up the surviving weird creatures and get them to a sanctuary where people can appreciate them in peace. A military bounty hunter has more brutal plans for the world’s cryptids.

Longerline: Dash Shaw, the comics artist and indie animator behind 2016’s enjoyably bizarre My Entire High School Sinking Into the Sea, returns with Cryptozoo, which is similarly stilted, wild, and unpredictable. Opening on a dreamy sex scene, where partners Amber (Louisa Krause) and Matthew (Michael Cera) get naked in the woods at night and dream about an ideal hippie future of world peace and equality, the film takes a grotesquely bloody turn almost immediately. They live in an ugly world that doesn’t respect high ideals and groovy vibes. Cryptid-hunter Lauren Grey (Lake Bell) certainly knows it: ever since childhood, when a dream-eating Japanese creature called a baku rid her of nightmares, Lauren has been trying to protect cryptids from capture, exploitation, and slaughter.

It’s a difficult job, both because the locals in sites around the world tend to capture cryptids for nefarious purposes, and because Lauren’s opposite number Nick (Thomas Jay Ryan) follows her around the world, scooping up her finds for the U.S. military. He wants the baku in particular because he believes it could be used to erase “the dreams of the counterculture,” and end left-wing protests for good. Lauren winds up chasing the baku just ahead of him, with the help of the gorgon Phoebe (Angeliki Papoulia), their aging idealist patron Joan (Grace Zabriskie), and the untrustworthy mercenary faun Gustav (Peter Stormare).

What’s Cryptozoo trying to do? The film is nominally an adventure story, complete with gunfights, fistfights, cryptid-on-cryptid slaughter, and a quest that ends badly for an awful lot of humans and creatures. But it also has a strong anticapitalist and anti-authoritarian streak that extends not just to the military-industrial complex, but more generally to humanity’s relationship with animals in general. When Phoebe first sees the soon-to-open Cryptozoo, the sanctuary where Joan is housing dozens of oddities, some with human intelligence, the gorgon is deeply disappointed. She points out that it looks more like a shopping mall than a refuge. And it does — it’s full of strip-mall stores and carnival sideshows, with Lauren boasting that they sell toys modeled after every confirmed cryptid. The garish zoo may not be her ideal form of protection, but it’s necessary, she says — it has to earn money to support itself.

While the Cryptozoo itself is built around that compromise between idealism and practicality, Joan is a purebred pie-in-the-sky type whose worldview revolves around love. She’s in a supportive, passionate relationship with one of her cryptids, and she’s convinced that the world’s problems can be solved with more of these kinds of connections. But she and her fellow preservationists may be benefitting more than the cryptids. The film eventually suggests that trying to contain them isn’t doing them any favors. Shaw acknowledges Lauren’s heroism in standing up to the predators who see every creature and person around them in terms of profit. But even she comes in for harsh criticism from Nick, who feels she’s doing the work both for her own peace of mind, and for the raw thrill.

- Google Ad Manager Launches Programmatic Email Ads

Google Ad Manager has quietly published documentation for a beta version of an advertising tag for email newsletters.

Email ads are cookie-proof. They do not depend on third-party tracking cookies for targeting. The end of tracking cookies in web browsers (as soon as 2025) has publishers and advertisers searching for new channels.

Email’s targeting capability could be the primary reason GAM is adding support. - eCommerce website solutions that drives salesccording to HubSpot, 80% of online shoppers stop doing business with a company because of poor customer experience. When all of your competition is also selling online, the shopping experience you offer your customers will be a critical differentiator.

- The Best WordPress Hosting Solution in AustraliaEach of our WordPress hosting solutions are fine-tuned, blazing fast and are ready for you! Starting a WordPress website has never been easier with our free 1-click WordPress installation, enterprise-grade security and an assortment of tutorials and helpful guides to get you started, all backed by our 99.9% uptime guarantee.

- Multilingual WordPress Sites to Reach a Global AudienceIf you are seeking to broaden the reach of your WordPress site to target an international audience, the following discussion on the leading multilingual WordPress plugins will be of interest. The plugins to be covered include WPML, Polylang, Weglot, TranslatePress, and GTranslate.

- How to Reset Forgotten Root Password in RHEL SystemsThis article will guide you through simple steps to reset forgotten root password in RHEL-based Linux distributions such as Fedora, CentOS Stream, Rocky and Alma Linux.

- VMware NSX Multi-tenancy; True Tenant Isolation?What is VMware NSX multi-tenancy? Historically multi-tenancy in VMware NSX was a Tier-0 gateway, otherwise known as the provider router, with one or many child Tier-1 gateways.

- How To Install Elasticsearch On RunCloudElasticsearch is a powerful, open-source search engine and analytics platform for storing, searching, and analyzing large volumes of data in real time.

- WooCommerce vs BigCommerce: What’s the Best Choice?If you’re starting an online store, one of the first decisions you’ll need to make is the eCommerce platform you’re going to use.

- Top WordPress Backup Plugins to Safeguard Your Website Data and Ensure RecoveryGiven the abundance of backup plugins available, the process of selecting the most suitable one can be daunting. This article aims to examine prominent WordPress backup plugins such as UpdraftPlus, BackupBuddy, BlogVault, among others.

The quote that says it all: “We can only greet the strange and unusual with love. And if we show them love, they will return love. And love will spread and envelope all the beings on our diverse, wondrous world.”

Does it get there? Cryptozoo’s morals can feel hazy amid all the action and incident, which feels more focused on communicating its characters’ widely varying personalities and goals than in finding a commonality between them. That leaves the narrative feeling more realistic than the average adventure story, but also messier and more prone to distractions, like a subplot around Phoebe’s impending marriage that doesn’t amount to much. The cryptid-protectors aren’t a unified or even focused group, they’re a handful of temporary allies who don’t fully agree on methodology or purpose, except when the situation gets serious.

The pacing also varies widely — the opening woodsy idyll feels like an unrushed short story, with Matthew poised naked atop the high Cryptozoo fence as just one lovely dream-image in a long sequence of them. But a clash between Lauren and Nick over a Russian bird-woman hybrid called an alkonost feels more like an episode out of Raiders of the Lost Ark, complete with Belloq swooping in to grab the idol after Indy does all the hard work. The film moves back and forth between action and dream-logic, and between espousing high ideals and watching people suffer as they try and fail to enact them. It’s certainly a cynical story — Shaw’s script has little faith either in his heroes’ ability to save the day, or in their good intentions in trying.

What does that get us? Much like My Entire High School Sinking Into the Sea, or for that matter like any good outsider art, Cryptozoo winds up as a window into a decidedly uncommercial mind, and a form of storytelling that isn’t the practiced, polished committee effort that comes out of animation houses like Disney and DreamWorks. It’s rare to see American animation aimed solely and specifically at adults, but Cryptozoo is noticeably focused on an arthouse audience — not just due to the kid-unfriendly sexual and violent content here, but due to the entire project’s philosophical bent and complicated point-of-view shifts.

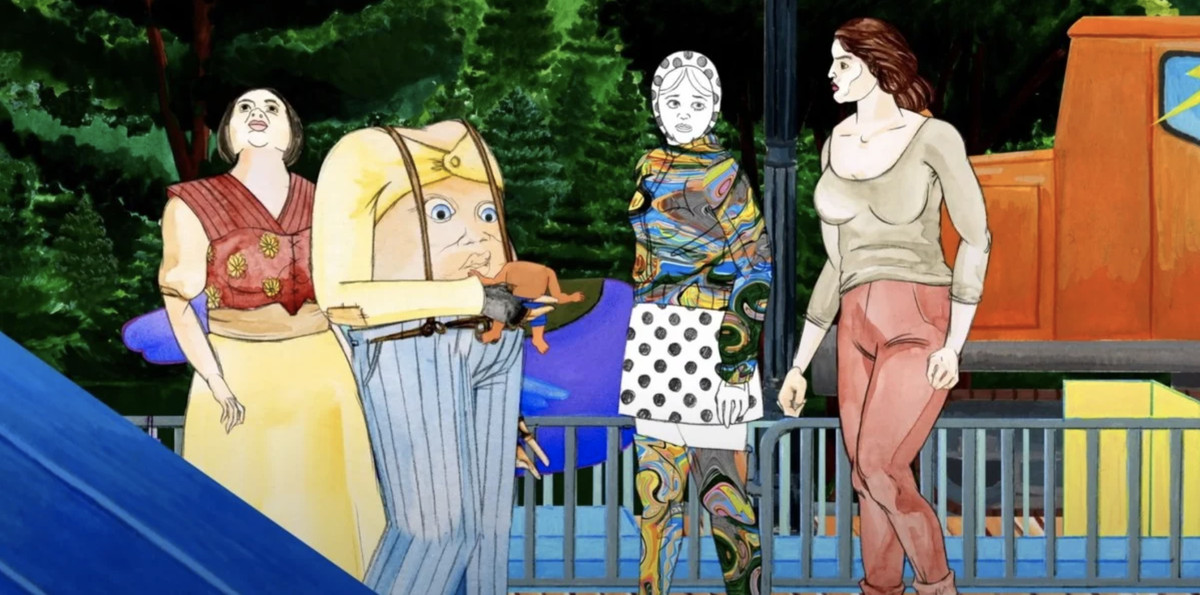

And after generations of increasingly processed and visually elaborate films from those outlets and others imitating them, the rough hand-drawn feel of projects like Cryptozoo can be shocking. It’d be easy to call it ugly, but it’s more accurate to call it idiosyncratic. Certainly the visuals bear much closer examination, to see where the textures of paints and pencils give the images a rougher and more specific feel, or where shifts from one style to another — like the difference between the raw contours of Lauren’s face and the fine-lined detail of Phoebe’s snake-hair — give the protagonists even more visual character.

At times, the character movement in Cryptozoo recalls Indonesia’s wayang puppetry, with rigid figures moving largely around the joints. Some sequences veer into a completely different style, like the beautiful light show put on at one point by a series of sentient light-creatures. Nothing about where the story is going or how it’ll get there stylistically can be taken for granted. That’s one of the biggest joys of Shaw’s projects — the sense of something new and different happening, of that anti-capitalist, anti-conformist, anti-containment bent that stretches throughout the story also extending into every aspect of the film’s aesthetics.

The most meme-able moment: Cryptozoo is full of startling moments and oddball visuals that creative memers could certainly repurpose, but maybe the most obvious ones come when Phoebe’s head-snakes bite people. The victims aren’t just poisoned, their flesh revolts and distorts, going full Akira. The image is a good setup for an “Oh no, the consequences of my own actions!”-style meme.

When can we see it? Cryptozoo is now widely available for digital rental or purchase via streaming platforms like Amazon and Vudu.